Good Performance vs. Bad Performance — and now WHAT

by Christos Tsolkas

Major societal, market, and economic disruptions can make performance assessment challenging. Just as it is difficult to assess progress in life after a rough turn, it can be tough to figure out how to judge progress after an abnormal event.

For example, COVID shut down a big chunk of healthcare companies worldwide for six months in 2020. However, the latter half of the year ultimately made up for those losses with record gains. 2021 was challenging with personnel fatigue, resignations, inability to cover the demand, operational breakdowns, and the like. Which reality was the true one? What will be the new paradigm? The old rules do not seem to apply.

Likewise, companies can have scandals, disastrous rollouts, failed leadership, bankruptcy, location change, and a host of other disruptions that can make traditional measures meaningless. The important thing is not to pretend those measures still matter or throw up hands in helplessness. Instead, businesses need to figure out which performance measures would be most helpful in their growth and survival. Anything less can finish a company off for good.

Counting & accounting

“Why measure” — mainly why measure up — and “what are the ways one can measure” were the fundamental questions I tried to answer in the previous two articles.

In a nutshell, one (organization or individual) can measure absolute or relative performance vs. the Past or the Target (call it ambition or potential). We know the Past is given while the Target represents the future, our “wish.”

These types of measures and assessments have significant implications for business. Corporate performance is difficult to assess or predict in most cases fully, and those measures can seem arbitrary depending on circumstances.

In 2018, the executives of the New York Rangers NHL hockey team took an unusual step. They wrote a public letter to the fans telling them their plan to tear down the team and build it back up. They explained how they would do it and how long it would take and asked fans for patience.

Sports fans are not known for patience, but they stuck by the Rangers, in large part because the team said, “Here’s how you should measure our progress,” and the team actually met those expectations. In addition, they restocked with great talent and began to look like a team that could go all the way shortly.

In Year 3 of this five-year plan, the owner fired everyone in the executive offices, shocking the sports world. Why? Because the team had failed to make the playoffs for the third year in a row. The owner’s measures differed from the executive team and perhaps even the players and fans. But, as usual, the owner won.

Who was right? There’s one way to measure success in sports — championships. But only one team can be champion, and repeat champions are rare. So does this mean every other team is a failure?

Assessments can be skewed in ways that disguise problems. For example, GE showed a positive performance improvement quarter-over-quarter for years. Too good to be true? It must indicate some level of “advantageous selection” of the numbers that shareholders, employees, analysts, and the media were not inclined to question. Or it is a result of immense pressure to sacrifice the short-term vs. the longer one. Yet, all suffered when GE’s business performance fell dramatically.

Morale can rise or fall depending on what gets measured. Departments can progress compared to the Past or be “failing” compared to the Plan or other external measures.

The challenge is to identify performance measures that actually help improve performance. For best, most consistent results, I think these measures should be standardized and assessed relative to each other. After consideration and study, I’ve come up with the following four simple dimensions:

- Progress (Absolute metric vs. the Past)

- Achievement (Absolute metric vs. the Plan)

- Implementation (Relative to competition metric vs. the Past)

- Strategic Fit (Relative metric to other players too but vs. the Plan)

Let’s examine how the variables offer a picture of performance and a direction for improvement.

The Four Dimensions

- Progress. It is your own progress vs. yourself only. You look back, take counts, laugh, cry, and move on. Using only such a lens, you omit the context, the conditions, what’s happening in the world or the market, and obviously, consider your potential. Heading Sales departments in the Past, I must confess that this was one of my yes-but excuses when trying to explain the miss of the budget. “We were short but look; We grew compared to last year.”

- Achievement. It results from your efforts vis a vis the absolute target you have set beforehand. How did I make it? Was it good enough vs. my expectations? Once more, the exclusive employment of such a measure does not reconcile the environment, the others, the market, the actual conditions.

- Implementation. In this case, the performance measure is comparative. You look at the result of your work in the Past vs. others (i.e., your competitors) in the same period. A typical example is the Share of Market (SoM) metric. Growing SoM most probably indicates that you do well in implementing your strategy. Such a measure puts you within the context to look successful even when your absolute performance might be weaker.

- Strategic Fit. If you achieve or exceed your future relative target, you look mighty, and apparently, it can indicate that your strategy works. A typical example of such a metric is the quarterly guidance on Earnings per Share (EPS) and its achievement when compared with several players within a given vertical.

All evidence out of practice and research supports the argument that none of the above in isolation can suffice to explain what happened and, most importantly, what needs fixing going forward.

Beauty Lies In The Eyes Of The Beholder

How would the cockpit of those four metrics categories look under different scenarios? I know every organization is different, with its background, boundaries, specificities. The context in any given case is so fundamentally important. However, this is a humble experiment to tabulate all scenarios in a simplified manner and provide possible actions worth considering.

Let me take as an example scenario 11.

Absolute performance, both vs. previous period and budget (i.e., Achievement), is weak. However, the relative performance looks promising, and the competitive position improves. What has happened? Perhaps a bear market, a sudden disruption fueled by externalities. It seems like the strategy works; you beat the competition as planned, despite the difficulty. Not reaching the budget while improving competitiveness might mean that you have been in an overspending situation or the budget was too ambitious. A relook at the resources is worth considering — at least in the short run.

More analysis, explanations, and ways to use the model are available.

Turning Around the Business

Improving performance in a turnaround sense starts with identifying which of the four dimensions is lagging. The clarity gained can make it easier to formulate a plan, sell that to critical stakeholders and follow through.

It can still be a daunting shift.

John F. Kennedy once said, victory has many fathers, failure only one.

When it comes to performance improvement, however, organizations have many excuses. Some will insist that the problems cannot be addressed quickly. There’s a strong desire to persist in old habits at old set points.

The organization may decide to make performance improvements but fails to implement or execute its strategy in other cases.

Strategy or execution falls.

Yet, there are many stories of companies that do undergo dramatic turnarounds. For example, Apple famously went from a niche tech player to the most dominant company in America because of its rigorous assessment of its performance failings.

Likewise, Best Buy looked at how it struggled to adapt to online shopping and figured out how it could establish a new way to play and win the game. Basically, it allowed consumers to match any price they could find online and leveraged the advantages of physical location to teach and guide consumers more directly.

Marvel Comics was one of the most exciting turnarounds in the past 20 years. The business failed a few decades ago, as print comic book sales faltered next to video games and movies, particularly Marvel’s rival DC Comics.

Marvel had massive intellectual property, however, and over the next few years, it learned to leverage that IP on film with tremendous stories. Accumulating studio clout and financing, the company kept thinking bigger and bigger. In addition to exploring stand-alone films, it began to bring all its characters together in a series of mega-films. After selling to Disney, the company has not stood still but continues innovating and exploring options. For example, it has recently begun to produce creative new twists on its old stories in the streaming limited series format. As a result, audiences felt surrounded by Marvel and entertained.

It’s critical for companies that attempt a second act to become more rigorous, more flexible, and more directed than ever while also understanding that failure to live up to its own new performance standards is inevitable and vital.

CONCLUSION

When I reflect on why performance matters and why so many businesses, leaders, and people feel both a drive for improvement and great confusion about achieving it, I can think of four main drivers.

- Ego. Whether an individual or a company, many of us like to win.

- Money (to secure funding/ income). By showing our performance favorably, we can help get the backing of people who might finance us or hire us to do the job right.

- Social norms. It’s also hard for individuals to forego comparisons and live without the need to assess and improve performance. Social norms are compelling, both in the breach and the alignment.

- Expectations and rules. For better or worse, every company and leader must live up to expectations around performance. However, it’s essential to keep those expectations balanced with what the company decides really matters.

Making those decisions is hard, and it helps to have sage and active support. This is where Boards kick in. Boards care about the overall health of the company. Is the company performing up to expectations (markets, financially); is it operating safely for employees and customers; does the leadership team have a solid, achievable, and sustainable plan?

Most importantly, it’s critical to understand how perceptions of performance and relative weights on performance measures can dramatically shape or shake up a business. A company that’s been going well can lose its way when it changes assessments, or those assessments no longer matter. The same can happen with an individual.

The essential thing is awareness.

If performance is a river, then we are aided when we stand on the banks of that river and observe its peculiarities and effects, rather than throw ourselves into the current and get swept along.

CTjan22

==========================

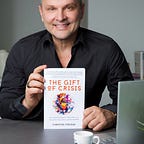

Christos Tsolkas is an Independent Business Advisor, Entrepreneur, and Author of the new book, The Gift of Crisis: How Leaders Use Purpose to Renew their Lives, Change their Organizations, and Save the World.

He has spent more than 25 years in positions of significant responsibility (general management, sales & marketing) with multinationals in the fast-moving consumer goods sector, leading senior teams to achieve high performance and change. His educational background is in chemical engineering & business, and he is dedicated to continuous learning.